La musica di montagna

- Antonio Forte

- Aug 19, 2024

- 6 min read

Mountain music. As soon as we opened the car doors, we were engulfed by the smell of wild mint. We were setting out for a long trek in the mountains of the Mainarde range, within the Parco nazionale d'Abruzzo, Lazio e Molise ('National Park of Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise'). Our goal was to get to the peak of Monte Marrone and to visit the cavelike hermitage that French artist Charles Moulin (1869--1960) had built and lived in there. Tracy Mackenna, the Museum of Loss and Renewal's director, had arranged to drop us off at the trail head in the morning and to pick us up around 5pm. I was joining fellow resident-artist Duncan Ross for the lengthy hike into the wilderness. We said our ciao's to Tracy and headed up the trail, the minty odor lingering with us for several meters as we clambered up the forested, limestone-pocked ankles of the mountain.

[Caption: Greeted by wild mint and baby snail shells. Creatively-rendered trail markers. Vibrant thistles aglow amongst the green and grey.]

After several hours hiking, spotting the intermittently-placed red and white trail markers, we eventually made it to a large, cleared out slope leading to a ridge that served as a vantage point to check our bearings. Unfortunately, the cleared slope had thrown us off from the trail: the area had been logged in a particular way wherein not every tree gets cut down, so that the remaining trees can re-seed, and that the land is not completely devastated/deforested. A type of sustainable forestry. However, we soon realized that what we thought were the red markers of the trail were simply red bands of spray paint marking the trees which were to be left uncut--in other words, every single tree in the small acreage we had been climbing, with Monte Marrone still looming in the distance above the ridge.

[Caption: Monte Marrone from the ridge. Bones found along the trail. Vistas of mountains, valleys, and far-off villages, through the trees.]

Decisions to be made while on a trail, especially an unfamiliar one, or a trail you think is a trail but is really not a trail anymore, are important. What may seem like a straight shot to the top ('let's just go UP') can hit sudden snags, like an unforeseen cliff dropping off just in front of you. Faced with this, we decided to stop for lunch at the edge of the cliff, sitting on some large rocks under the shade of some small trees. After eating our previously-packed provisions and chatting about art and life and hiking--well, what's the difference really?--we decided, based on how much time had elapsed and how long it would take us to hike back down to where we were to rendezvous with Tracy, to follow the ridge line across for a bit. The grassy open area suddenly gave way into a cool, darkened, forested incline. Leading down from the now-forested ridge, we realized we were following a trail, albeit unmarked by the red and white we were searching for. Some time went by, we paused at various points to quietly observe the remnants of a deer's presence, which we had inadvertently scared off; or to listen to the distant tinkering and tinkling of cow bells echoing up from the valley below us. As the afternoon wore on, we had to make another decision to turn back. I was a bit ahead of Duncan and had spotted something peculiar: a small length of rectilinear stone wall, sticking out in the dense forest. It was only a couple dozen meters further up the trail, marking what appeared to be an almost-dried-up mountain stream. We hunkered down here for a moment to rehydrate ourselves, not knowing that another creature had decided to do the same thing. We suddenly paused our conversation and stopped our movements. There was a large rustling coming from just beyond the little stone wall. Boar? Bear? I quietly retrieved the two metal hiking poles I had been carrying on the back of my rucksack, and handed one to Duncan. Just in case, I whispered almost inaudibly. Based on the sound of leaves and branches rustling, it was definitely something large. I perched myself upon the big round chunk of limestone I had been sitting on, craning my neck and scanning the rocks and brush frantically with my eyes. And then they appeared: just beyond some large rocks and fallen trees, a giant set of antlers.

[Caption: The movement of antlers (in the center of frame, just to the right of the larger tree).]

[Caption: We shuffled a bit too much, and the stag ran off, escaping up the mountainside.]

After the stag had bounded off, back up the mountain to escape the sounds we were making, I said, il cervo, penso ('the stag, I think'), trying to remember the word for male deer. The sun began to sink further behind the mountains. We headed back down, doing our best to follow the pseudo-trail, and to eventually find the marked trail we had hiked in on. The descent took a bit less time than the ascent, which we had estimated earlier that morning. We knew we were getting close to the trail head when we were yet again confronted by the odor of wild mint--we had made it back to the road where Tracy was picking us up. Sitting at the trailhead drinking water and eating some snacks while we waited, Duncan reflected, 'the mountain chewed us up and spit us back out.' I concurred. Perhaps our interaction with the stag was Monte Marrone's way of wagging its proverbial finger at us, further reprimanding our seemingly willy-nilly attempt at conquering its mighty heights in such a short time, and at such short notice. The mountain and its mysteries remain there for us, for a future climb.

[Caption: Duncan and I after our hike: chewed up, spit out, but in good spirits.]

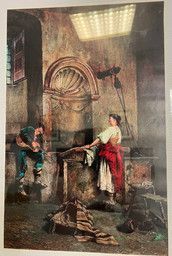

[Caption: Stopping at the bar in the neighboring village of Cerasuolo for a cold drink after our hike, we are met by more antlers and a painting of a zampogna and ciaramella.]

A day or two before our hike, we had made an appointment with Eugenio, one of the village elders who organized an 'unofficial' museum in Filignano. The vast collection of artifacts, photographs, artwork, and shelves full of countless binders containing a multitude of photocopied photographs, all documented the shared stories and local histories of Filignano and its neighboring villages. Eugenio was a seeming font of information, having spent forty years of his life collecting stories and objects for the museum. The museum is held inside Filignano's closed school (there are no longer enough children in the village to warrant it being open). We walked slowly alongside Eugenio, who stopped every couple of feet to point out a certain object and explain its significance or story. There were four of us visiting the museum with Eugenio: fellow resident-artists Katia Nethercot, Lotte de Schouwer, Duncan Ross, and myself.

[Caption: Some of the artifacts at Eugenio's museum, including an old bugle and fisarmonica ('accordion'). All of the labels are written in the Filignanese dialect.]

As soon as we entered into the front door, climbed up the stairs, and were confronted by the long corridor full of old objects, I was immediately reminded of my grandparents' house. At the back of it, on the brick wall above the wood stove, was a long shelf with similar objects from my grandfather's parents: old woodworking tools, a license plate, a set of bellows, hand-woven implements for beating dust out of carpets, black-and-white photographs...

[Caption: An old photograph of Molisan musicians. The caption reads, 'Italian Zampogna-players in the streets of London (around 1900).' Perhaps this is what my great-great-grandfather looked like in Paris around the same time--his daughter (my great-grandmother) was born in 1900.]

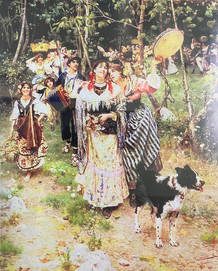

It was a miraculous experience to be surrounded by oddly familiar objects, the wood darkened and smoothed over with the patina of time and toiling of working hands; and especially by so many depictions and documentations of the musicians, musical traditions, and traditional clothing of Molise, of the mountains. The collector, curator, and caretaker of all of this, Eugenio, is an incredible, passionate person, doing important work. He is generous with his time and sharing his knowledge. As we walked back down the stairs to the exit, headed to the bar in Filignano to treat Eugenio to a coffee (which meant cocktail for him), I lingered on the stairs to converse with him. He walked with a cane, just like my grandfather. I mentioned I was a musician myself, having played the piano for thirty years, and the ciaramella now for exactly one. I warned him that if he heard some bad sounds coming down from Collemacchia, it was most likely me practicing. He chuckled and advised me to soak l'ancia ('the reed') in wine. Bianco o rosso? I asked ('white or red?'). He laughed heartily and responded, rosso.

[Caption: I musicisti montanari Molisani ('the mountainous Molisan musicians'). The Molisan instruments tend to include: tambourines, zampogne, ciaramelle, mandolins, lutes, guitars, and accordions.]

[Caption: La musica porta gioia ('music brings joy').]

Comments