Costruire strumenti, costruire musica.

- Antonio Forte

- Aug 3, 2025

- 7 min read

Constructing instruments, constructing music. When one arrives in Scapoli for the International Zampogna Festival, one must park ones car before entering into the little hilltop borgo. Every way one walks to get to the town center is uphill.

[Caption: Scapoli in the rain--beautiful in any weather.]

The skies were threatening rain when I arrived. I parked the car, and immediately a tiny grey FIAT pulled up and parallel parked in front of me. The driver got out and we greeted each other. He was drinking a beer and proceeded to light a cigarillo. He asked if I wanted any--a beer or a smoke. I declined both. A few sporadic drops fell from the sky. We both noticed, and I said, ho dimenticato un ombrello ed un impermeabile ('I forgot an umbrella and a raincoat.') He pointed to his hat and put on a vest. We both shrugged and chuckled a little. About fifteen minutes later I knew his life story: he was a musician, a percussionist, had a music studio at home, and pointed out each house we passed that used to belong to a relative of his, even the house of his grandparents in which he grew up with chickens in the backyard. As we made our way uphill to the town center, he shook my hand and entered the first open bar. I continued onwards. It began raining.

[Caption: The rain may not stop them, but a parking ambulance will.]

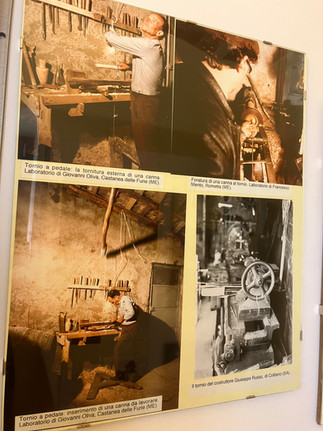

[Caption: Workshop and tools for constructing zampogne and ciaramelle.]

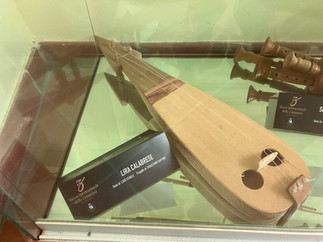

As the rain continued, I made my way through the narrow cobblestoned streets to the International Zampogna Museum. Once inside, I chatted with the young gentleman selling tickets, purchased a ticket, and was handed a tablet with which to walk around the museum and scan QR codes (every instrument in the collection has a QR code, allowing museum-goers to listen to short recordings of each one). The collection is exceptional, extensive, and contains examples of zampogne and ciaramelle from several different regions around Italy and related instruments from around the globe.

[Caption: My ticket to the International Zampogna Museum.]

[Caption: Various zampogne and related instruments from Italy and around the world, including two examples of duduks (bottom).]

After wandering around for a while, listening to the sound samples of as many zampogne as possible, I heard the chatter of voices, the clatter of chairs, and came to a small room set up for presentations. At one end was a large table covered with what first looked like ingredients for a weird salad, with some museum and park staff persons appearing to prepare their strange-looking salad with utility knives.

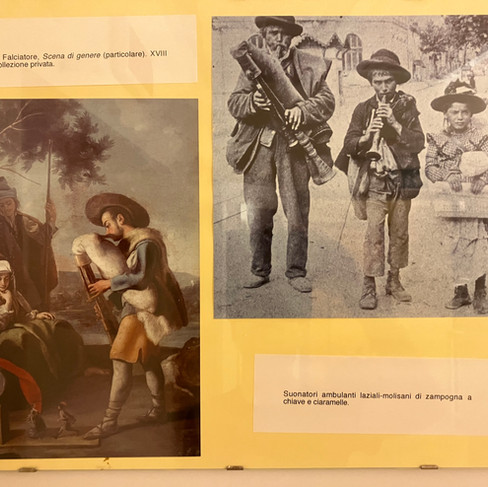

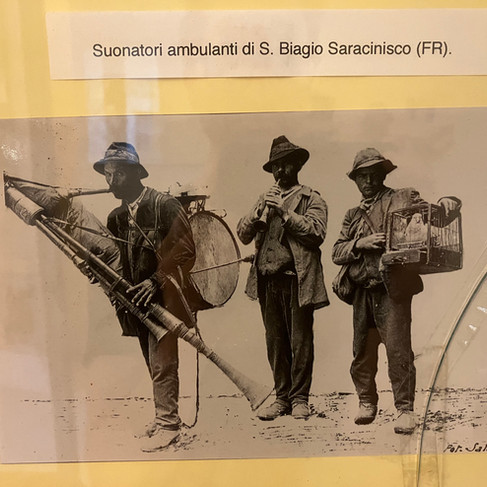

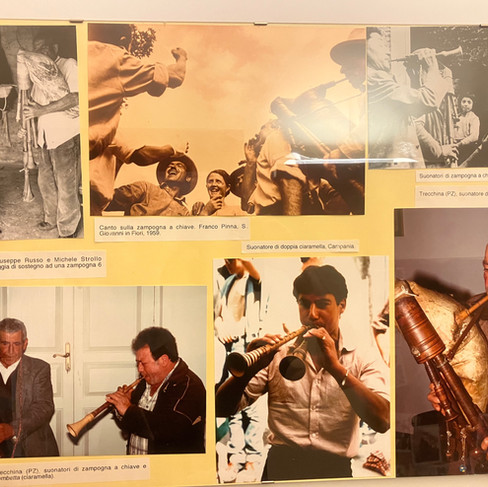

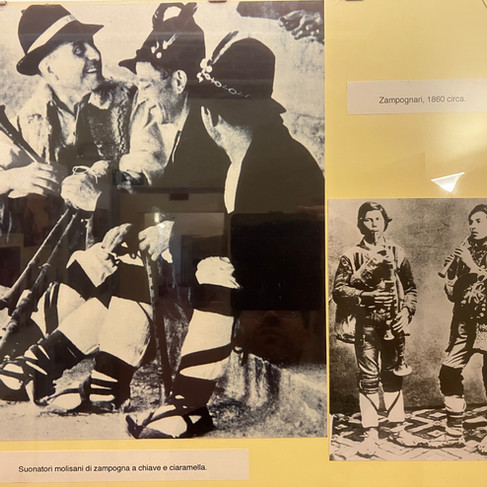

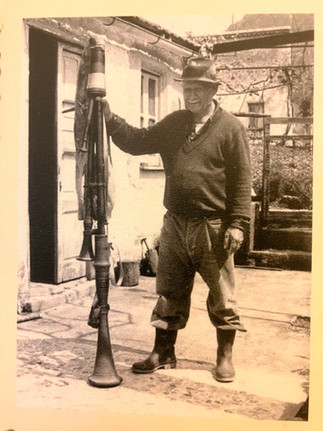

[Caption: Pictorial and photographic documentation of zampognari--zampogna players--and other accompanying musicians throughout history, as well as the workshop and tools (bottom right) traditionally used in the instrument's construction.]

I entered and was told to pull up a chair. The two presenters were from the Parco Nazionale d'Abruzzo e Molise Laboratorio ('the National Park of Abruzzo and Molise Laboratory) and were giving a presentation titled Tra suoni e Natura, 'Between Sounds and Nature'). I was immediately transfixed by what was transpiring: the stalks of zucchini plants were being used to construct wind instruments, something that our ancestors have been doing for tens or perhaps hundreds of thousands of years.

[Caption: Demonstrating the zucchini stalk instrument.]

[Caption: Doppi flauti etruschi in alabastro, 'Etruscan double flutes in alabaster.']

When I finished my museum visit, I made my way to the piazza, and there saw an old friend, Luigi Carini, whom I had met two years prior upon my first visit to Scapoli for the festival. He is an instrument maker and performer, and each year I purchase new ciaramella reeds from him. He was busy helping another ciaramella player fine-tune their out-of-tune reed, making careful adjustments with a surgical-looking knife, scraping fine layers from the surface of the reed, comparing the octaves of G with a tuner app on his phone. I told him I did not want to interrupt, and because of the rain would return to see him the next day.

[Caption: My arrival on the second day for the International Zampogna Festival coincided with the arrival of Gl'Cierv* and entourage...spaventoso! ('frightening!'). Gl'Cierv, dialect for il cervo,* 'the deer,' is a figure from a traditional and primordial ritual, perhaps Samnite or pre-Samnite in origin.*Click on the links for further information.*]

[Caption: Scapoli in the sunshine. Luigi and I, and his instruments--our yearly photo has become quite a tradition.]

The next day I returned to Scapoli. The sun was shining, fluffy, billowy clouds were floating by, and the mountains seemed to be smiling in anticipation of the day's musical events. I quickly found my way to Luigi's table in the piazza. He exclaimed L'italo-americano! ('the Italian-American!'), and we embraced, shook hands, and had a quick chat about the year gone by. He took out some ciaramella reeds, and I proceeded to test them out. I played the G scale (most, if not all ciaramelle are in the key of G, or sol in Italian), a few snippets of improvised or remembered melody, and compared the octaves. Troppo dura? ('too hard?') he asked, SÌ, dura, I responded, handing him back the reed. He gingerly and expertly scraped the surface with his reed-maker's knife. In addition to two ciaramella reeds, I purchased a new reed for my duduk.

[Caption: Some traditional, itinerant musicians playing accordion, castanets, ciaramella, and tambourine.]

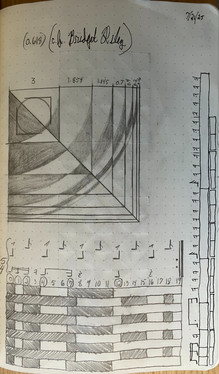

As musicians passed by Luigi's table, they each stopped to greet him and to take out their instruments for adjustments or new reeds. I could see things were getting busy at the festival, and quickly said my well-wishes and gratitudes to Luigi and his team, and made my departure. Over the next few days, I held in my mind the concept of constructing instruments, the rituals of the past (the deep past), and how music, instruments, music-making have been a continuous thread across cultures and throughout anthropological time...I contemplated the relationship tra suoni e Natura ('between sounds and Nature'), simple mathematical formulas, formulas for organic growth found in Nature, like the zucchini stalks used to make instruments, the Golden Section, its Greek symbol phi (φ), and its facsimile, the Fibonacci sequence. What would these forms of Nature sound like? I asked myself. To answer this question, I began making sketches in my sketchbook.

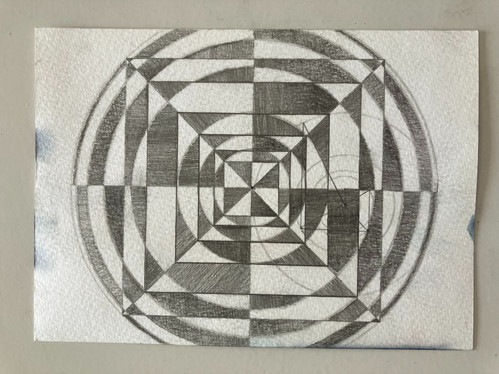

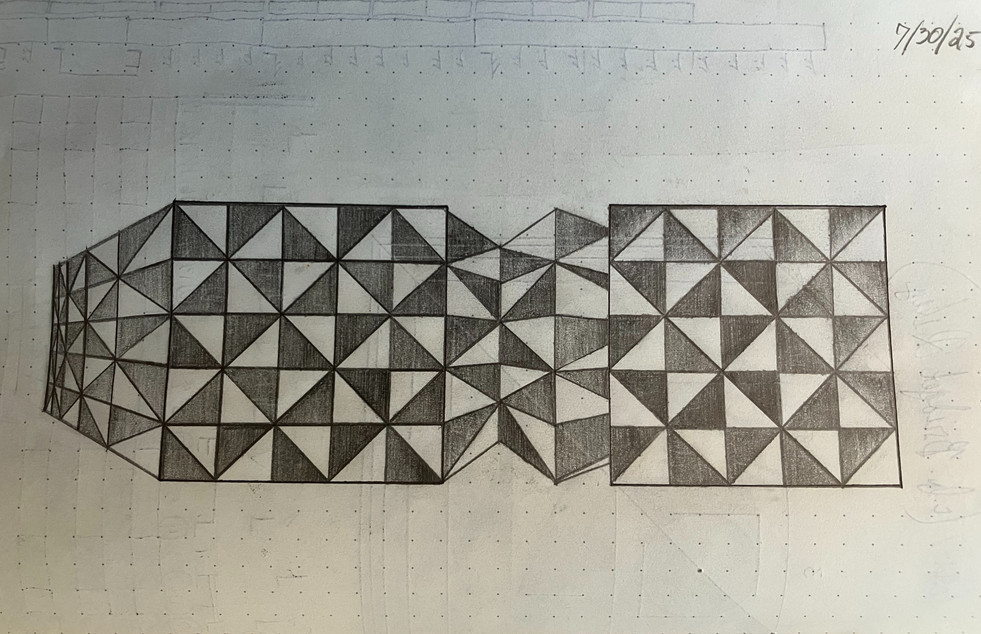

[Caption: Sketch of the Golden Section as the basis for geometric patterns and expressing the Fibonacci sequence with rhythmic structures (top left). More 'fun with phi,' aka using 0.618 as the multiplier for radii of concentric circles, and circumscribing squares (top right), leading to geometric patterns and superimpositions (middle). Practicing perspective drawing techniques using similar geometric patterning (bottom).]

Now that the visualizations and sketches were finished, what would these formulas and geometric patterns sound like? I set about constructing several computer instruments, which I call apparatus, to carry out these experiments. The first apparatus, number 345 (for obvious reasons [see number 5]), uses the ratios set down by Pythagoras and his followers for the division of the octave, giving very close approximations to modern equal temperament of the musical octave. I titled this apparatus i toni pitagorici, Italian for 'the Pythagorean tones,' which is also translated into Oscan (middle title) and Greek (top title). The indicators (red 1, yellow 3, green 4, and turquoise 5) in the middle represent the base 1=do and its following pitches (mi, fa, and sol), which are rhythmically divided by 3-4-5. That is, yellow is pitched at the 3rd ratio (mi=81:64), green at the 4th ratio (fa=4:3), and turquoise at the 5th ratio (sol=3:2). The base pitch is 100Hz, so that using the ratios one can calculate each of the other notes in the scale (for example, to calculate sol=3:2, one multiplies 100Hz by 3 then divides by 2, which equals 150Hz).

[Caption: Apparatus 345: Pythagorean Tones, used to demonstrate the Pythagorean rhythmic and pitch structures, based on Pythagorean ratios of the division of the octave and the 3-4-5 triangle.]

The next apparatus, numbered 346, utilizes the equation for Bezier curves. I will not pretend to understand this equation, or how it functions, but was able to insert it into MAX/MSP and construct this apparatus which simplifies the outputs of the equation into lines on a two-dimensional (x,y) coordinate plane. The colors don't correspond to the pitch, per se, in the same way as in apparatus 345, but are simply a scaling of the pitch spectrum 50Hz--555Hz onto RGB values, 0--255. Each sound is synthesized in real-time using a digital replication of a Buchla-inspired method: a dual oscillator, with variable waveform between sine and triangle waves, going through a wavefolder into a Lowpass Gate. The (x,y) coordinates resulting from the Bezier formula are then averaged together to determine the pitch (therefore the color and thickness of the lines being visualized), the rhythm (both the envelope and tempo of individual notes), and the panning (left/right stereo field). There is also a second version wherein I attempted to changed everything from whole-numbers into decimals, in the hope of producing actual curves. Instead there is an ellipse and some quite peculiar loops of pitches and rhythms, colors and lines.

[Caption: Apparatus 346: Bezier Curves. Attempts one and two.]

Comments